Meet the Leaders

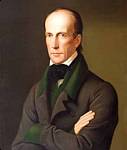

Archduke John Baptist Joseph Fabian Sebastian von Hapsburg (1782-1859)

by Unterleutnant Gary McClellan,

Kaiserlich-Königliche Österreichische Armee

Like many in the NWC, my start was not in computer wargames, but in board games. In those days, my favorite game by a fair margin was the old Avalon Hill game War and Peace. The Napoleonic era had a special appeal. One of the aspects that caught my eye was the colorful variety of leaders. Of course there were the usual  suspects: Napoleon, Wellington, Kutusov, and the like. Yet, I was already inexplicably drawn to the nation with the white counters, that being (of course) Austria. The names there were exotic and tantalizingly unfamiliar: Hiller, Bellegarde, Schwarzenberg. Among these colorful names, one stood out as bland and prosaic: John. Yet, somehow I found myself wondering, "Who is that guy?" Now, with the release of Campaign Eckmühl, the curiosity struck again. I took the time to dig deeper, and found a man of surprising interest. As wargamers, it would be easy for us to say "poor-to-fair commander" and dismiss him, but there was more to the man than that.

suspects: Napoleon, Wellington, Kutusov, and the like. Yet, I was already inexplicably drawn to the nation with the white counters, that being (of course) Austria. The names there were exotic and tantalizingly unfamiliar: Hiller, Bellegarde, Schwarzenberg. Among these colorful names, one stood out as bland and prosaic: John. Yet, somehow I found myself wondering, "Who is that guy?" Now, with the release of Campaign Eckmühl, the curiosity struck again. I took the time to dig deeper, and found a man of surprising interest. As wargamers, it would be easy for us to say "poor-to-fair commander" and dismiss him, but there was more to the man than that.

The Archduke John was the youngest son of Emperor Leopold II of the Holy Roman Empire. As such, he was the grandson of Empress Maria Theresa as well as the nephew of Joseph II, and he followed closely in the tradition of these two "enlightened despots." The reigns of Maria Theresa, Joseph II, and Leopold II had seen a steady if limited progression from a near-feudal state into a more modern nation. Reforms in the rights of peasants, economics, justice, administration, Church-State relations, and other issues marked this period. John's life would reflect his support for "progressive" causes. This would especially influence the course of his life after the death of his father and the accession to the throne of John's oldest brother Francis, who was not progressive and in many ways attempted to reverse the trends of the previous 50 years.

John first appeared on the pages of History in 1800. Napoleon had defeated an Austrian army at Marengo in June, forcing a temporary truce, the Convention of Alessandria. Emperor Francis was not yet prepared to sue for peace with France, and the remainder of the year was spent preparing to renew the war. Austria planned to strike back not in Italy, but in Germany. Command of this venture was first offered to the Archduke Charles, a seasoned commander, but he turned it down. Command of the army was then vested in the 18-year-old Archduke John. He was assigned able subordinates, Feldzeugmeister Baron Franz Lauer as second-in-command and Colonel Weyrother as chief-of-staff. In the first  battle, at Ampfing, John's forces drove back two French divisions under Ney. John's army then pushed on toward the main French position at the crossroads of Hohenlinden. Whether or not it was John's own creation, the Austrian plan for that day was the sort of over-complex, touchy plan that often appeals to inexperienced generals, calling for four separate columns to maneuver through the snow-choked woods and converge on the French position. As could be expected, confusion and delay made hash of the plan, and the Austrian army was badly beaten by the French under Moreau.

battle, at Ampfing, John's forces drove back two French divisions under Ney. John's army then pushed on toward the main French position at the crossroads of Hohenlinden. Whether or not it was John's own creation, the Austrian plan for that day was the sort of over-complex, touchy plan that often appeals to inexperienced generals, calling for four separate columns to maneuver through the snow-choked woods and converge on the French position. As could be expected, confusion and delay made hash of the plan, and the Austrian army was badly beaten by the French under Moreau.

John next appeared prominently in the aftermath of the disaster of Austerlitz. He played a role in the army reforms initiated by his brother Charles, especially in the development of the Landwehr. When the showdown came in 1809, John was given command of the Army of Inner Austria, deployed along the border with the French-ruled territories in Italy. John was able to force battle with Prince Eugène de Beauharnais at Sacile; Eugène had been handicapped by Napoleon's insistance that he not concentrate his forces too early, thereby giving the Austrians a casus belli. The Austrians won the day at Sacile, scattering Eugène's army and potentially throwing Napoleon's whole scheme into disarray. However, even before word of John's victory could reach Napoleon, the latter had gained victory in the Bavarian campaign over the Archduke Charles. John, his position made untenable by the French forces moving down the Danube, retreated towards the Danube valley himself, with Eugène following. John eventually retreated into Hungary, to gather the forces of the "Hungarian

Austerlitz. He played a role in the army reforms initiated by his brother Charles, especially in the development of the Landwehr. When the showdown came in 1809, John was given command of the Army of Inner Austria, deployed along the border with the French-ruled territories in Italy. John was able to force battle with Prince Eugène de Beauharnais at Sacile; Eugène had been handicapped by Napoleon's insistance that he not concentrate his forces too early, thereby giving the Austrians a casus belli. The Austrians won the day at Sacile, scattering Eugène's army and potentially throwing Napoleon's whole scheme into disarray. However, even before word of John's victory could reach Napoleon, the latter had gained victory in the Bavarian campaign over the Archduke Charles. John, his position made untenable by the French forces moving down the Danube, retreated towards the Danube valley himself, with Eugène following. John eventually retreated into Hungary, to gather the forces of the "Hungarian Insurrection." Eugène attacked at Raab. John had a strong position, on a hilltop with a river flowing in front; for a time, his forces gave a good account of themselves. Eventually a force of French cavalry under Grouchy was able to ford the river to the south and defeat the Hungarian Insurrectionist Cavalry, flanking John's position. Eugène was then able to make one last push, defeating John. Following this, John was unable to move his force to link up in time with his brother Charles, while Eugène's forces joined Napoleon and played a key role at Wagram. This failure of John to reinforce his brother would poison relations between the two of them for years to come.

Insurrection." Eugène attacked at Raab. John had a strong position, on a hilltop with a river flowing in front; for a time, his forces gave a good account of themselves. Eventually a force of French cavalry under Grouchy was able to ford the river to the south and defeat the Hungarian Insurrectionist Cavalry, flanking John's position. Eugène was then able to make one last push, defeating John. Following this, John was unable to move his force to link up in time with his brother Charles, while Eugène's forces joined Napoleon and played a key role at Wagram. This failure of John to reinforce his brother would poison relations between the two of them for years to come.

With the Austrian defeat in 1809, the Archdukes Charles and John withdrew from the direction of military affairs. John eventually moved to Graz, in Styria, where he would achieve the greatest successes in his life. He participated in Court affairs only intermittently, generally in opposition to the policies of Metternich. However, he took a keen interest in the development of Styria. He helped develop the trade and transportation of the hitherto isolated town of Graz. He was also greatly intested in Styric culture, founding the Joanneum, the first museum in Austria dedicated to the public. During this time he also shocked the Court by marrying the daughter of a local postmaster. Nearly 200 years later he is still a beloved figure in the history of Graz, and the central plaza of the town is built around his statue.

John might well have lived out a quiet retirement, had it not been for the Revolutions of 1848. Emperor Francis had long since died; his son Ferdinand "the Benign" occupied the throne but was mentally handicapped, and not really fit to rule. Francis had arranged for a Council of State to assist Ferdinand; in his will, Francis made it explicit that two persons were not to serve on the Council: the Archdukes Charles and John. The leadership of the Council was left to the less-capable Archduke Louis. In 1848, the Austrian Empire was not spared the wave of revolutions breaking out across Europe, in France, Italy, Germany and beyond. If anything, Austria's crisis was worse, with the ethnic Magyars, Croats, and others demanding greater rights and threatening nationalist revolt. Ferdinand and his advisors, fearing they might become trapped in a Revolutionary Vienna and share the fate of Louis XVI, departed; Ferdinand appointed "my dear uncle" John as Regent. The spread of revolution in the German states soon led to the calling of the "Frankfurt Parliament" of 1848, an attempt at establishing a pan-German constituent assembly. Archduke John was elected its President. The post was invested with next-to-no power, however, so John's practical influence was slight.

John's influence as Regent of Austria was essentially removed when counterrevolutionary forces pacified Vienna. Ferdinand abdicated, and the nation was gradually brought under the control of the new Emperor, Franz Josef. With the Austrian Imperial forces working to tighten control over the ethnic minorities, the expressly pan-Germanic Frankfurt Parliament became alienated from the Hapsburgs. The Parliament offered the crown of "Unified Germany" to the only other logical contender, King Frederick William of Prussia. This monarch refused to accept a crown "from the gutter," i.e. by election. Prussia would gain the leadership of Germany two decades later, through Bismarck's policies of "Blood and Iron."

After the dissolution of the Frankfurt Parliament, John retired once again to Graz, where he died in 1859.

Sources

Books:

- Robert A. Kann, A History of the Hapsburg Empire, 1526-1918. University of California Press, 1974.

- Gunther E. Rothenburg, Napoleon's Great Adversary: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792-1814. Spellmount, Staplehurst, 1995.

- James R. Arnold, Marengo and Hohenlinden: Napoleon's Rise to Power. Arnold, Lexington, VA, 1999.

Websites of Interest:

Next Page

Return to Index

suspects: Napoleon, Wellington, Kutusov, and the like. Yet, I was already inexplicably drawn to the nation with the white counters, that being (of course) Austria. The names there were exotic and tantalizingly unfamiliar: Hiller, Bellegarde, Schwarzenberg. Among these colorful names, one stood out as bland and prosaic: John. Yet, somehow I found myself wondering, "Who is that guy?" Now, with the release of Campaign Eckmühl, the curiosity struck again. I took the time to dig deeper, and found a man of surprising interest. As wargamers, it would be easy for us to say "poor-to-fair commander" and dismiss him, but there was more to the man than that.

suspects: Napoleon, Wellington, Kutusov, and the like. Yet, I was already inexplicably drawn to the nation with the white counters, that being (of course) Austria. The names there were exotic and tantalizingly unfamiliar: Hiller, Bellegarde, Schwarzenberg. Among these colorful names, one stood out as bland and prosaic: John. Yet, somehow I found myself wondering, "Who is that guy?" Now, with the release of Campaign Eckmühl, the curiosity struck again. I took the time to dig deeper, and found a man of surprising interest. As wargamers, it would be easy for us to say "poor-to-fair commander" and dismiss him, but there was more to the man than that. battle, at Ampfing, John's forces drove back two French divisions under Ney. John's army then pushed on toward the main French position at the crossroads of Hohenlinden. Whether or not it was John's own creation, the Austrian plan for that day was the sort of over-complex, touchy plan that often appeals to inexperienced generals, calling for four separate columns to maneuver through the snow-choked woods and converge on the French position. As could be expected, confusion and delay made hash of the plan, and the Austrian army was badly beaten by the French under Moreau.

battle, at Ampfing, John's forces drove back two French divisions under Ney. John's army then pushed on toward the main French position at the crossroads of Hohenlinden. Whether or not it was John's own creation, the Austrian plan for that day was the sort of over-complex, touchy plan that often appeals to inexperienced generals, calling for four separate columns to maneuver through the snow-choked woods and converge on the French position. As could be expected, confusion and delay made hash of the plan, and the Austrian army was badly beaten by the French under Moreau.