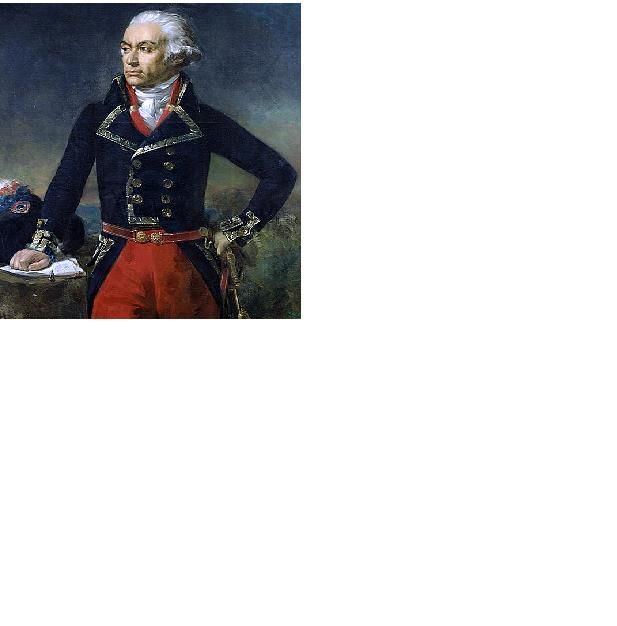

At the outbreak of the Revolution, seeing the opportunity for carving out a new career, he went to Paris, where he joined the Jacobin Club in 1789. The death of Mirabeau, to whose fortunes he had attached himself, proved a great blow. However, opportunity arose again when, in his capacity as a lieutenant-general and the commandant of Nantes, he offered to march to the assistance of the National Constituent Assembly after the royal family's unsuccessful flight to Varennes.

In 1790, Dumouriez was appointed French military advisor to the newly established independent Belgian government and remained dedicated to the cause of an independent Belgian Republic.

Minister of War, Louis Lebègue Duportail, promoted Dumouriez from president of the War Council to major-general in June 1791 and attached him to the Twelfth Division, which was commanded by General Jacques Alexis de Verteuil.

He then attached himself to the Girondist party and, on 15 March 1792, became the French minister of foreign affairs. Dumouriez then selected Pierre LeBrun as his first officer for Belgian and Liégeois affairs. The relationship between the Girondists and Dumouriez was not based on ideology, but rather based on the practical benefit it gave to both parties. Dumouriez needed people in the Legislative Assembly to support him, and the Girondists needed a general to give them legitimacy in the army.[1] He played a major part in the declaration of war against Austria (20 April), and he planned the invasion of the Low Countries. His foreign policy was greatly influenced by Jean-Louis Favier.[2] Favier had called for France to break its ties with Austria. On the king's dismissal of Roland, Clavière and Servan (13 June 1792), he took Servan’s post of minister of war, but resigned it two days later on account of Louis XVI's refusal to come to terms with the National Constituent Assembly, and went to join the army of Marshal Luckner. After the émeute of 10 August 1792 and Lafayette’s flight, he gained appointment to the command of the "Army of the Centre". At the same moment, France's enemies assumed the offensive. Dumouriez acted promptly. His subordinate Kellermann repulsed the Prussians at Valmy (20 September 1792), and Dumouriez himself severely defeated the Austrians at Jemappes (6 November 1792). After these military victories, Dumouriez was ready to invade Belgium to spread revolution. He was a true revolutionary in the sense that he believed that nations which had undergone a revolution, in this instance France, should give aid to oppressed countries. As his plans were largely limited to Belgium, this tunnel vision sometimes prevented him from acting in the most logical fashion as a commander.[3]

Returning to Paris, Dumouriez encountered popular ovation, but he gained less sympathy from the revolutionary government. His old-fashioned methodical method of conducting war exposed him to the criticism of ardent Jacobins, and a defeat would have meant the end of his career. To the more radical elements in Paris, it became clear that Dumouriez was not a true patriot when he returned to Paris on 1 January 1793 and worked during the trial of Louis XVI to save him from execution. Dumouriez had also written a letter to the Convention scolding it for not supplying his army to his satisfaction and for the Decree of 15 December, which allowed the French armies to loot in the territory they had won. The Decree insured that any plan concerning Belgium would fail due to a lack of popular support among the Belgians. This letter became known as “Dumouriez’s declaration of war”.[1] After a major defeat in the Battle of Neerwinden in March 1793, he made a desperate move to save himself from his radical enemies. Arresting the five commissioners of the National Convention who had been sent to inquire into his conduct (Camus, Drouet, Bancal-des-Issarts, Quinette, and Lamarque) as well as the Minister of War, Pierre Riel de Beurnonville, he handed them over to the enemy, and then attempted to persuade his troops to march on Paris and overthrow the revolutionary government. The attempt failed, and Dumouriez, along with the duc de Chartres (afterwards King Louis Philippe) and his younger brother, the duc de Montpensier, fled into the Austrian camp. This blow left the Girondists vulnerable due to their association with Dumouriez.